The Impact of Craftsman Architecture in Columbia, South Carolina 1900-1930

Thursday, March 2nd 2023

Proponents of the Arts & Crafts movement—a 19th-century English aesthetic born out of disdain for the socially detrimental aspects of the Industrial Revolution and the excessive ornamentation of the later Victorian Age—today, if they were on Instagram, would be considered among the most successful of social influencers. Their philosophy celebrated the original, the novel, and a recalling of a pre-capitalist era in which the individual artisan left his (and her) handcrafted marks on art, decorative arts, and architecture—manifestations of skill lost in the wake of machine-made, banal details that offered mass-produced goods to a growing middle class. By the turn of the 19th century, the once-nascent movement spawned wider-spread converts, including tastemakers in the United States who ultimately shaped the Craftsman style, which in its purest form sought to harmonize form and function while strengthening connections between one’s home and nature. Ultimately, and not surprisingly, while Craftsman architecture and decorative arts flourished for more a generation, its rise in popularity through those years can be attributed to some of the very infrastructure and technology that the earliest Arts & Crafts founders eschewed—mass production and formulaic style. The popularity of homes for “everyman” in the form of bungalows, cottages, and American Foursquares resonated with socially ascendant middle-class families, scores of whom were establishing lives for themselves in suburbs throughout American from 1900 through 1930.

In Columbia, Craftsman-inspired houses came to characterize every suburbs established just outside the original boundaries of the Palmetto State’s capital city during the early 20th century. Valued as sturdy and affordable, these then-contemporary residences exuded a charm through architectural details that paid homage to the tenets of the larger, national, movement. Elements such as exposed rafter tails, heavy brackets, building materials including wood, stone, masonry, and stucco were employed in ways large and small, depending on location and who was building (or having built) residences in the new neighborhoods of Elmwood Park, Waverly, Shandon, Hollywood-Rose Hill, Earlewood, Cottontown, and Melrose Heights and Oaklawn, to name just a few.

However, while some of the finer, more customized houses may have employed artisans who rendered uniquely designed and executed architectural details, most Craftsman style residences were erected using modern technology and, in some cases, very modern production and marketing techniques such as those employed by companies like Sears, Aladdin, and Honor-Bilt in their kit homes. In Columbia, and, most likely in other cities throughout the United States, local architects, developers, and lumber supply companies copied, partially mimicked, or derived inspiration from mass-marketed building plans. Ultimately, the Craftsman architectural aesthetic architecture that resulted in physically attractive and well-thought-out buildings and desirable details, became so popular that it trumped the larger philosophical and social concerns of the preceding Arts & Crafts movement’s founders. However, although capitalism eclipsed those ideals in some ways, the mass popularity of the look and feel of the Craftsman style enjoyed nonetheless shaped a uniquely American story that today continues to attract a healthy following among homeowners of all backgrounds, ages, and demographics.

The Craftsman Allure

Well over a century after they were embraced as a new architectural design, Craftsman style houses resonate with today’s homeowners, who value them for their distinctive details and the materials used in their construction. Located in Columbia’s Melrose Heights neighborhood, this Craftsman bungalow at 1301 Gladden Street exudes character through contrasting masonry elements of red and yellow striated (wire -cut) brick; wood elements including faux half-timbering, heavy brackets and exposed rafter tails, and a merging of different sash forms.

|

|

Devaluing the Victorians

The later Victorian period employed manufacturing technology and excessive ornamentation and often formulaic designs, considered as uninspired and “vulgar” by those who espoused the individuality and virtuousness of the Arts & Crafts movement that later gave rise to the Craftsman aesthetic. This unidentified Columbia residence, featured among grand homes in Artwork of Columbia, SC by the Gravure Illustration Company in 1905, arguably typifies what the Craftsman movement sought to rectify. Historic Columbia collection, HCF2008.41 A-I

The Bungalow Form

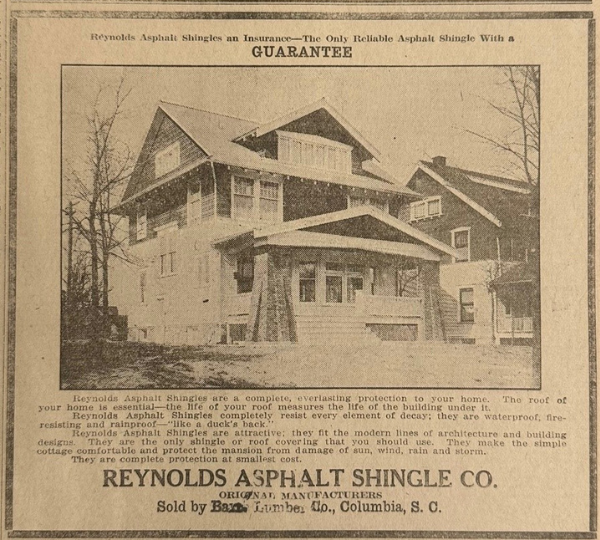

Typically characterized as being a one to one-and-a-half story residence with an asymmetrical façade, a low roofline with deep overhangs, and often exposed structural woodwork, bungalows became synonymous with the Craftsman style. This advertisement, run in The State newspaper for the Reynolds Asphalt Shingle Company in 1914, illustrates a higher-end bungalow of two-and-one-half stories, and a building similar in scale to that of 2306 Devine Street.

|

|

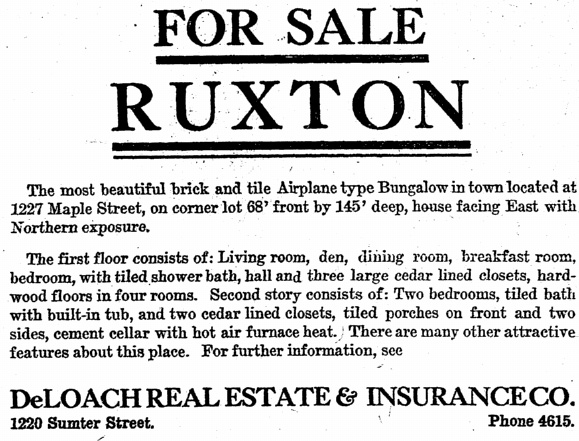

The Airplane Bungalow

Also referred to as a “California” bungalow, airplane bungalows draw their name from their partial second story or “cockpit” that projects above the wings of the roof. This form of bungalow is pretty rare in Columbia, where only eight examples have been identified, and of those, five stand in Melrose Heights at 1215, 1217, 1227, 1228, and 1318 Maple Street!

The Craftsman Cottage

The average size of bungalows and cottages could vary from around 1200 to 3,400 square feet, depending on several variables, including whether the half story was improved or used simply as an attic. Seen here with its original aesthetic intact, this large Craftsman cottage at 1500 Gladden Street, incorporates a jerkin-head (clipped gable) roofline, faux half-timbering, as well as a juxtaposition of red-brown bricks and locally sourced granite to arrive at a dramatic Tudor or Norman-influenced appearance.

It’s What’s on the Inside that Matters, Too

Inside, Craftsman-inspired homes often featured a breakfast nook, a butler’s pantry, parlor, dining room, kitchen, two or more bedrooms, one or more fireplaces. Other amenities frequently found were front, and side porches, a rear service porch, and, on American Foursquare houses, a sleeping porch in temperature climates. Shown here is a floor plan from a 1916 mail-order house.

On the Right Tract

Some Craftsman houses in Columbia were architect commissioned. Others were based on plans purchased through the mail, such as from architects like Lila Ross Wilburn in Atlanta, or out of magazines such as Ladies Home Journal. Many may have been familiar to property developers and contractors (who could be the same business), who procured them at local lumber yards, such as the Allison & Driggers Lumber Company, which by 1925 advertised in The State as carrying “plans and specifications, along with pictures of bungalows, cottages, two stories, apartments and store buildings.”

Mass-Marketing and Efficiently Manufacturing the Craftsman Ideal

Throughout the United States stand examples of what could simultaneously be the antithesis of the philosophical underpinnings of the Arts & Crafts movement’s celebration of the individual craftsperson and the pinnacle of the average American to enjoy—at least to some degree—a measure of individuality in their home’s aesthetic, albeit through modern mechanization, marketing, and transportation. Enter the “kit home,” championed for its budget-minded design and its predictability in construction—an equation that resulted in tremendous sales for such companies as Sears, Honor-Bilt, and Aladdin

|

A Kit Home from Closer to Home

Beyond companies such as Aladdin, Honor-Bilt, or Sears, smaller companies, such as North Charleston’s Dixie House Company, which ran this advertisement in The State newspaper in May 1921, provided prospective homeowners with kit-sourced residences. Several neighborhoods throughout the capital city feature examples of nationally available kit homes. How many locally sourced kit homes are present remains to be seen.

Don't miss

Palladium Tour | Craftsman Columbia

This year's Palladium Tour on Sunday, April 16, 2023, will showcase six Craftsman properties nestled within the Melrose Heights-Fairview-Oaklawn neighborhood. In between tour stops, participants will have the opportunity to peruse the offerings of Melrose's Art in the Yard festival during this self-paced walking tour. The tour will conclude with a block party on Hagood Avenue where participants will enjoy a taste of the neighborhood and the southern hospitality that defines much of our community.