Another Perspective in Matriarch Mary Cantey Hampton

Monday, March 26th 2018

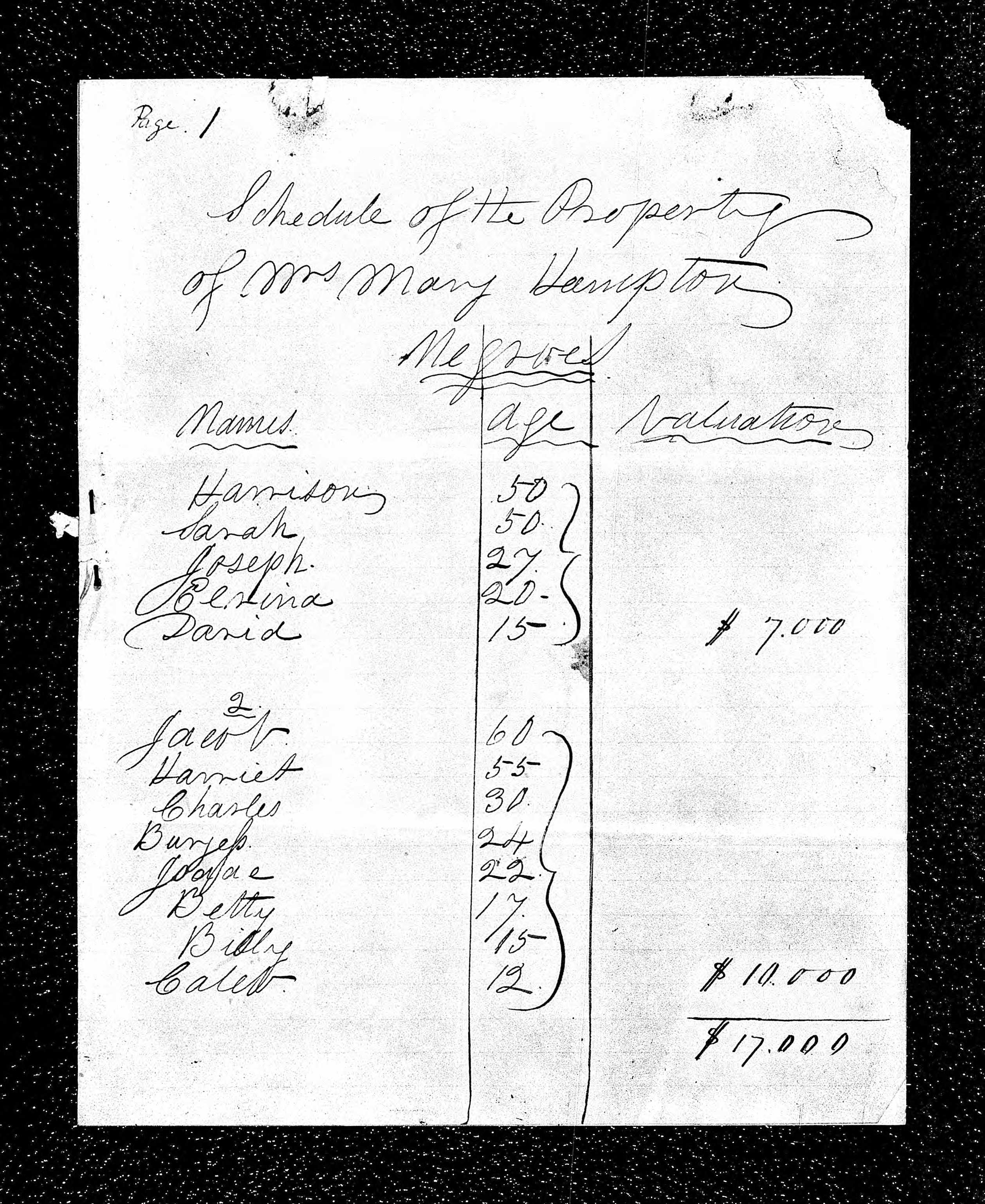

Historic Columbia collection, HCF 1999.1.1

In 1970, following months of rehabilitation and restoration work, the circa-1818 Hampton-Preston Mansion opened as the centerpiece of the Midlands Exposition Center, one of three major state-run facilities established for celebrating the 300th anniversary of South Carolina’s founding. At that time, reverence for the site’s association with Wade Hampton I drove many decisions on how the site was presented to visitors. Far less emphasis was placed on Mary Cantey Hampton, Wade I’s third wife, who, ironically, spent far more time at the urban estate, from 1823, when he bought the property until her passing in 1863, forty years after his death.

Indeed, Mary Cantey Hampton, ranks as one of the better-known Columbians, thanks in part to her association with her husband, who at one time was considered one of the South’s richest planters. Due to her status and wealth, information about Mary Cantey Hampton, as the family the matriarch, comes in many forms – through her material wealth—personal effects, silver and her surviving residence, portraiture, photographic, and anecdotal and official documents, such as her last will and testament. It is the latter instance that prompts investigation into and discussion of her role as the leader of her family. In this role, Mary Cantey Hampton would have held great authority, particularly in the strategic appropriation and application of daily and longer-term assets—including human property.

Upon her death in 1863, the woman who had overseen the growth and nurturing of her own children and grandchildren—many at her urban estate—made one final decision through her will that dictated the disposition of enslaved men, women and children for whom she held legal title. It remains unknown as to whether Mary Cantey Hampton’s actions had permanent consequences for the persons she enslaved, as a scant two years later they were free following outcome of the Civil War. However, the subsequent inventory, or “Schedule of the Property of Mrs. Mary Hampton,” provides arguably the greatest sources of information for some of the people in the family’s bondage.

Fortunately, the names of the enslaved are listed and presumably in groups denoting family ties:

Harrison (50) Sarah (50) Joseph (27) Elvina (20) David (15) Jacob (60) Harriet (50) Charles (30) Burges (24) Isaac (22) Betty (17) Billy (15) Caleb (27) Shandy (75) Flora (65) Frank (35) Shandy (30) Sappho (22) Abby (19) Anise (33) Moss (11) Minerva (9) Isaac (7) Jim (5) William (3) Rebecca (2 ½) Sarah (3 Months) Eleanor (60) Robert (33) Peter (45) Henry (53)

Collectively, these 31 people were valued at $33,000. Other significant “line items” included $57,000 in bonds and stocks and $20,000 in silver. Coupled with her will, this schedule illustrates the immediate fate of each person, as they were legally transferred through inheritance gift to 11 of Mary Cantey Hampton’s relatives, including children and grandchildren. Thanks to this remarkably detailed document, Historic Columbia can better identify enslaved people who worked at the Hampton-Preston estate, at least up until 1863, when Mary Cantey Hampton died. The presence of names and ages, in addition to the households suggested by the grouping of names, further humanizes the historic site’s past, which was a complex web of relationships that played out for decades before freedom came for people of color in 1865.

Learn more about the 200th anniversary of the Hampton-Preston Mansion.