Searching for Motel Simbeth

Friday, February 22nd 2019

On 20 October 1955, Jet, a national weekly digest with a primarily black audience, published the expose “SOUTH CAROLINA’S PLOT TO STARVE NEGROES.”

The six-page piece described efforts by White Citizens Councils in Clarendon and Orangeburg counties to create an “economic squeeze” on black community members. The goal of the squeeze was to “‘starve’ some 3,000 Negroes in the two counties who are NAACP school petition signers, members or sympathetizers [sic]” by refusing to sell them foodstuffs, denying them opportunities to labor for wages, and refusing to approve farm-related bank loans. The article raised national awareness of the backlash African Americans faced following the Brown v. Board of Education decision (which included the Briggs v. Elliott case from Clarendon County). It also suggested that readers could help by sending money and supplies to NAACP Secretary Mrs. A.W. Simkins at 2025 Marion Street, Columbia, South Carolina. Mrs. Simkins is now better known as Modjeska Monteith Simkins, who served as the state conference secretary from 1941 until 1957.

Jet readers from across the United States and beyond responded with thoughts, prayers, checks large and small, and promises to send food and clothing. A summary of these 315 letters, compiled by Simkins, along with many of the original responses have been digitized by South Carolina Political Collections at the University of South Carolina, the primary repository for the papers of Simkins. But how did Simkins’s name and address come to appear in Jet? Her response to one Jet reader, stated that it was a “move from the heart of Mr. Simeon Booker,” who authored the piece, and not a planned action by the NAACP.

At the time, Simeon Booker (1918-2017), a black reporter who joined Jet in 1954, was less than two months removed from his first major reporting experience in the Deep South: the murder of black teenager Emmett Till and subsequent trial and acquittal of his murderers. Booker and Jet photographer David Jackson attended the viewing, where Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, asked that the casket be opened and permitted Jackson to photograph her standing stoically behind her son’s disfigured body. Its publication launched the civil rights movement into the national consciousness. The violence of Till’s lynching and the cruel absurdity of the courtroom proceedings made one thing clear: white supremacy was still the law of the South.

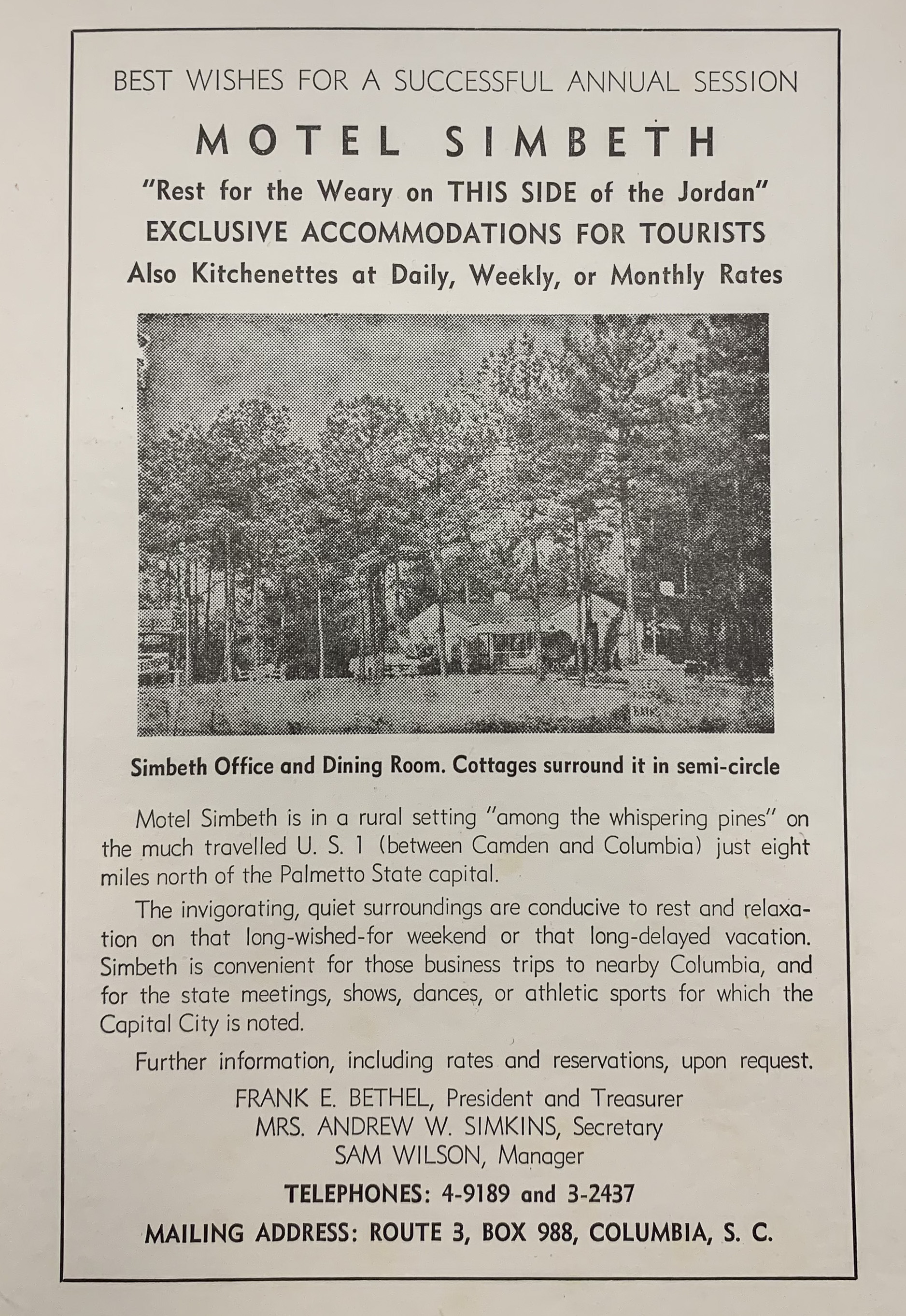

After the Till case, Booker and another Jet reporter coordinated with Rev. Albert C. Redd and L.A. Blackman, president of the Elloree branch of the NAACP, to interview subjects for the economic squeeze piece. Their base of operations was Motel Simbeth, located eight miles north of Columbia on US-1 (present-day Two Notch). The motel, co-owned by Modjeska Simkins, likely opened a few months earlier. It offered two things that Columbia’s other black-owned hotel, Hotel Nylon, could not: privacy and access to Mrs. Simkins, one of the state’s most visible and connected civil rights activists. In a 1976 interview with historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Simkins recalled this about the group’s stay:

"They disguised themselves in poor farming area attire and went into the area after DeLaine's church was burned to investigate, and happened to get out just in time to protect their lives from attack. They didn't finally end until about sunset; it was a winter evening. So they came back to Columbia and they were staying at the motel that I was running at that time. And we were sitting around talking when Simeon Booker said, "I just wish there was something we could do about this thing, how we could help these people better being pressured this way." And then he said, "Maybe we could put a little box in Jet, just a little enclosure and tell people to send assistance into this area." He said, "Now, you would have to have a place if goods come in to store them until you could get them distributed." I said, "Well, I have a vacant store, a good-sized place that we could use, and my brother has a vacant space in one of his buildings. And I believe the space would not be a problem." So he put this little box in Jet magazine, and in the course of a week or ten days money, canned foods by the ton and clothing started coming in. At the same time Adam Clayton Powell saw this little thing in Jet, and he invited me up to talk at Abyssinian Church. And his church sent scads of relief materials."

— Modjeska Monteith Simkins, interviewed July 28, 1976. (The 20 October issue of Jet also included Booker’s article on the arson of Reverend Joseph DeLaine’s church in Lake City.)

Although numerous interviews with Simkins exist in the public record, she rarely mentioned the motel or its potential role in the civil rights movement. The State newspaper reported on three separate incidents of gunfire at the motel in 1956, and Simkins filed a statement about an additional shooting in 1963. Despite the intermittent violence and covert visits by civil rights figures with proverbial targets on their backs (Martin Luther King, Jr. once visited during the 1950s), the motel was also an oasis. It’s only known depiction, which appeared in postcard form and in advertisements, show a main structure set amongst pines and surrounded by cabins, with signage designating it as a space for black guests. The motel’s motto, “Rest for the Weary on this side of the Jordan,” reinforced the perception that travelers need not wait until the next life to find rest and relaxation—they merely needed to stay at Simkins’s rural property.

A month after Booker’s stay at the motel, Columbia hosted the 15th annual meeting of the South Carolina Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (SC NAACP). Simkins, as the state secretary, likely compiled the program, which featured the motel’s most elaborate advertisement on the very first page. Attendees, no matter where they stayed that weekend, surely kept the motel in mind for future travel. Yet the motel’s most promising revenue stream came from an outside source—the Negro Motorists Green Book.

Victor H. Green established the Green Book, as it was commonly called, in 1936. He recognized that African Americans, while increasingly able to afford cars and leisure travel, would also experience what historian Gretchen Sorin called an “uncertain landscape" that was "composed of white spaces where black people were forbidden or unwelcome.” The first edition, which appeared in 1937, featured only New York locations, but its second expanded to states across the south, including South Carolina. Columbia locations appeared in the book from 1938 until its final edition, published in 1966-1967. Although other similar guides were published, including the “Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring,” none experienced the success of the Green Book, which Green, and later his wife, Alma Green, issued for 30 consecutive years.

Motel Simbeth appeared in the Green Book from 1956 until 1961. It was the only Columbia location to ever receive a “recommended” star from the publishers, although it’s unclear if this was similar to a paid sponsorship. By 1956, the guide only featured overnight accommodations and restaurants, but previous years included nightclubs, beauty parlors and schools, barber shops, taxi companies, nightclubs, and taverns. Several of these locations still stand today. Unfortunately, Motel Simbeth was demolished sometime after 1965.

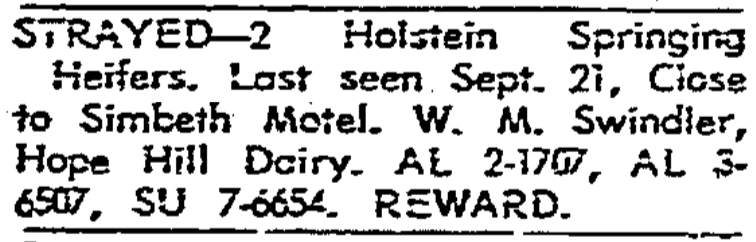

Simkins’ niece, Dr. Henrie Monteith Treadwell, remembers the motel well. But more elusive is where it once stood along US-1 (present-day Two Notch Road). With the construction of I-277 and Columbia Mall, the area has changed dramatically. One advertisement that ran for several days in 1963 provides a clue:

Hope Hill Dairy was once located off Farrow Road somewhere close to today’s Greenview, Farrow Hills, and Farrow Terrace neighborhoods, and it may have expanded east towards US-1 prior to the construction of I-277. If Motel Simbeth was located on an adjacent or nearby parcel, it may have been situated on the northwestern side of US-1 between Fontaine and Decker roads. For now though, the search is ongoing.

Header image: Matchbooks from Motel Simbeth reading “’REST for the Weary on THIS SIDE of the Jordan’ MOTEL SIMBETH EXCLUSIVE ACCOMODATIONS FOR COLORED TOURISTS” on the front. Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2012.4.2 A-B

Have a story of your own?

Historic Columbia welcomes any additional information about sites found in the Green Book. Please visit our Green Book page for a complete listing of both demolished and extant structures.