Modjeska Simkins' History

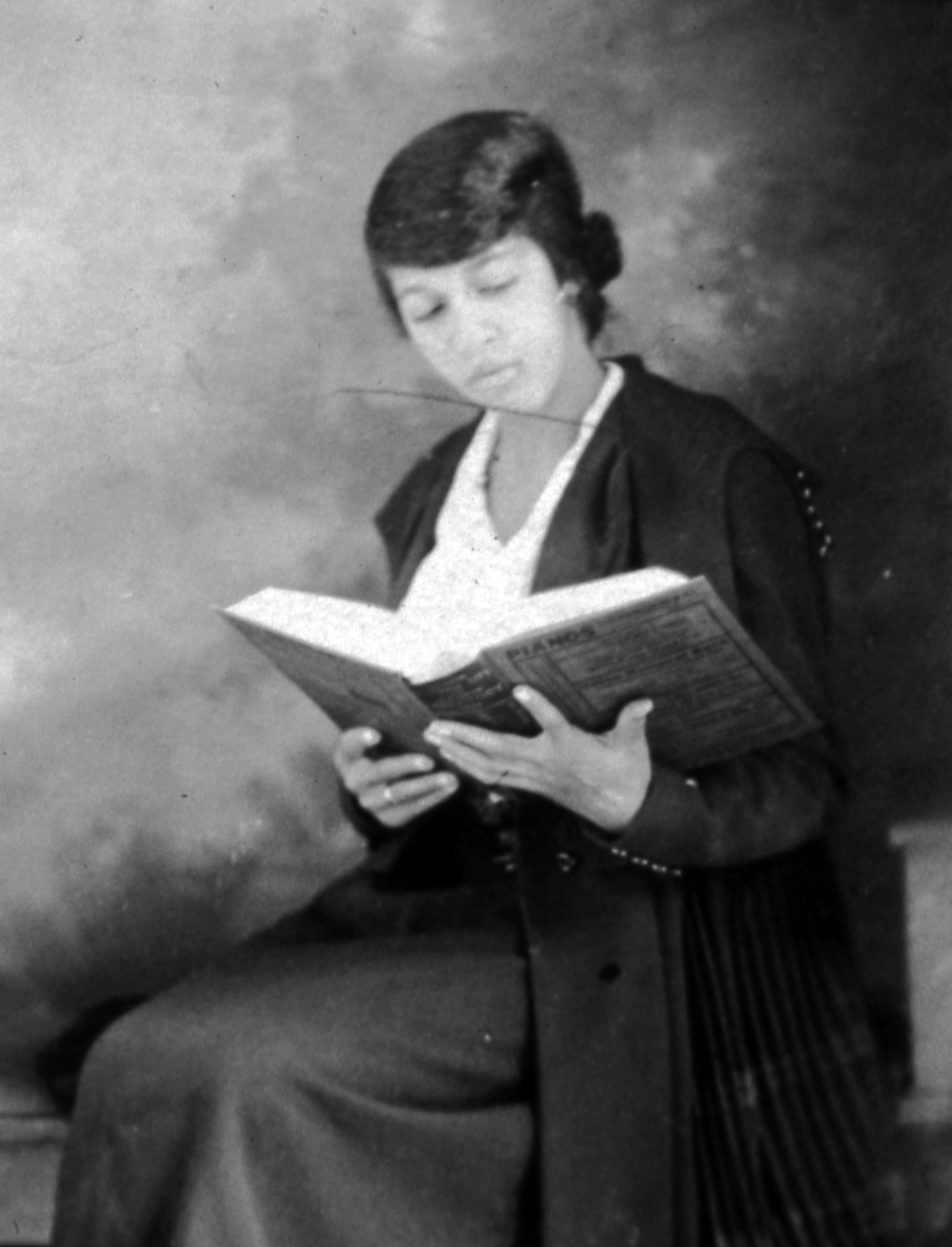

Modjeska Monteith Simkins was born in Columbia, SC, on December 5, 1899 to Henry Clarence Monteith and Rachel Hull. Although her activism extends across more than seven decades and numerous causes, she is best remembered for her leadership during the early Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina.

Who was Modjeska Simkins?

Educator at Booker T. Washington High School

Modjeska Monteith Simkins' experiences as a teacher at the segregated Booker T. Washington High School and as the Director of Negro Work for the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association (SCTA) in the 1920s and 1930s positioned her as an authority on the issues African Americans faced in South Carolina—namely discrimination in the form of unequal or restricted access to education, healthcare, economic opportunities, and the ballot. The supremacy of white culture and privilege, codified in Jim Crow laws and protected through widespread disenfranchisement of Black citizens, seemed insurmountable after the quashing of Columbia’s NAACP branch in the early 1920s. Her work with the SCTA, in particular, exposed the middle-class Simkins to the abject poverty and poor health of rural African Americans, a result of pervasive and systemic inequality. Simkins, in this instance and throughout her life, chose action over inaction and moral anger over despair.

Secretary of the South Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP

By 1941, Simkins moved to organize African American resistance on a broad scale. That year she assumed the position of secretary of the South Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP (SC NAACP), an organization she helped organize two years earlier when representatives from the state’s seven local branches met to coordinate their efforts. Simkins also convinced budding activist and newspaper publisher, John H. McCray, to move his Charleston Lighthouse to Columbia, a move she and her husband Andrew Simkins helped finance. The merger of McCray’s paper and the Sumter Informer in 1941 marked the emergence of a Black press that continually advocated action over appeasement, even in the face of white reprisals. The popularity of The Lighthouse and Informer in South Carolina’s Black community helped mobilize support for state and national NAACP efforts and kept citizens informed of ongoing injustices in communities across the state. Simkins and McCray were the driving forces—financial and editorial—behind the paper until its closure in 1955.

Civil Rights Activist

Simkins, firmly established in the leadership of the NAACP, joined with other activists to challenge South Carolina’s continued flouting of established law. Key cases included the fight for equal pay for black teachers (Duval v. Seigneus and Thompson v. Gibbes et al.), the fight to end the all-white Democratic primary in South Carolina (Elmore v. Rice), and the fight to end segregation in public schools (Briggs v. Elliott), with Simkins and Rev. Joseph A. Delaine co-authoring the original petition for the latter. Thurgood Marshall later argued Briggs alongside four other cases in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark ruling Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which effectively overturned the court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson which codified the practice of “separate but equal.”

The early Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina was more than court cases and an active Black press. Simkins spent the 1940s and early 1950s fundraising to establish a first-rate hospital in Columbia for African Americans. The Good Samaritan Waverly Hospital opened in 1952. Simkins was also particularly interested in coalition building with outside organizations, both Black and white. This was exemplified by her work as a senior advisor with the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). The SNYC, a radical coalition formed in 1937 as a youth branch of the National Negro Congress, whose work focused on economic and political equality, international solidarity with oppressed peoples around the world, and ending racial violence and police brutality. The peak of the SNYC's activity and influence was the Southern Youth Legislature held in downtown Columbia in 1946. The three-day event brought together students, labor activists, and internationally renowned orators, including W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Robeson, and would become a source of inspiration for activists in the decades to come. Simkins, along with John H. McCray and others, was instrumental in planning the conference.

The aspect of landmark victories, including Elmore v. Rice and Brown v. Board of Education,  that is rarely told is the reaction of white citizens against South Carolina communities and individuals fighting to enact actual desegregation. Columbian George Elmore lost his business and home. The petitioners in Briggs v. Elliott faced “economic terrorism” and actual acts of terror—Rev. Delaine’s home and church were burned, and he later fled South Carolina, never to return. John H. McCray, the editor for The Lighthouse and Informer, spent two months on a chain gang after being convicted of libel in 1950 in the lead up to the Brown v. Board decision. Here again, Simkins emerged relatively unscathed. Her family’s leadership in the Victory Savings Bank allowed Simkins to provide financial assistance to others in the movement. Simkins’ husband, Andrew, maintained a diversified real estate portfolio in Columbia that catered to African Americans, and Simkins later operated Motel Simbeth, which appeared in the Negro Traveler's Green Book. Differences with other organizers over tactics ultimately forced Simkins out of the SC NAACP. Her relationship with the SNYC and other left-wing groups with rumored ties to the Communist Party led to her name appearing in memos to the House Un-American Activities Committee.

that is rarely told is the reaction of white citizens against South Carolina communities and individuals fighting to enact actual desegregation. Columbian George Elmore lost his business and home. The petitioners in Briggs v. Elliott faced “economic terrorism” and actual acts of terror—Rev. Delaine’s home and church were burned, and he later fled South Carolina, never to return. John H. McCray, the editor for The Lighthouse and Informer, spent two months on a chain gang after being convicted of libel in 1950 in the lead up to the Brown v. Board decision. Here again, Simkins emerged relatively unscathed. Her family’s leadership in the Victory Savings Bank allowed Simkins to provide financial assistance to others in the movement. Simkins’ husband, Andrew, maintained a diversified real estate portfolio in Columbia that catered to African Americans, and Simkins later operated Motel Simbeth, which appeared in the Negro Traveler's Green Book. Differences with other organizers over tactics ultimately forced Simkins out of the SC NAACP. Her relationship with the SNYC and other left-wing groups with rumored ties to the Communist Party led to her name appearing in memos to the House Un-American Activities Committee.