James Clyburn Announces New Reconstruction Era Network

Monday, March 4th 2019

I am excited to be here today in support of the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park Act bill. With the goals of creating a Reconstruction Network that will enhance collaboration across SC, the region and the country.

In 2008, our organization began the process of rehabilitating a home that was constructed in 1869, at the height of the Reconstruction Era in Columbia. As we considered how to best interpret the site, there were two major incidents that guided our decision.

First, that year we offered a public program about the end of the Civil War, during which Dr. Bernard Powers spoke about the post-emancipation experience of African Americans - highlighting leadership positions and governmental shifts that occurred during that time. A long-time board member of Historic Columbia approached me after the program and asked, “why is this not a story that I have heard before?” The board member, an African American woman in her late 60s, was empowered by the stories, but truly shocked by the lack of information made available to her during her formative and into her adult years about the truth of Reconstruction.

Second, a year earlier our organization initiated a traveling trunk program, which took local history into the classroom. Following its successful inaugural year, we surveyed teachers to ask what historical periods they would like for us to tackle next. Where is the greatest need? Overwhelmingly the answer was: Reconstruction. Teachers cited the lack of resources available, the erroneous and misleading information in textbooks and their gaps in understanding based on a lack of attention given to this era in their own schooling.

Acknowledging the gaps in scholarship, as well as information for more than a century has grossly misrepresented this critical point in our history, we knew that we had the opportunity to transform the story at our historic site into one that could be both a corrective measure as well as a tool for enlightenment, for celebration and for reckoning. The major challenge that we had, and still have today, is that this Reconstruction-Era building was the family home of Woodrow Wilson, who lived with his parents and siblings in Columbia from 1869 to 1872. The home was preserved based on its association with Wilson and up to 2008, interpreted as a shrine to the 28th president. We changed that – quite dramatically – today it stands as the only local history museum in the country that focuses solely on the Reconstruction Era.

At this site, visitors learn that Columbia and Richland County, like the rest of the South and indeed the nation, were working out the meanings of freedom in a post-slavery society. At all levels of government—federal, state, and local—debates raged over questions defining American citizenship. All of Columbia’s 9,297 residents, both black and white, witnessed the profound political changes of Reconstruction. According to the 1870 census, 57% of the population was black or mulatto and 43% was white.

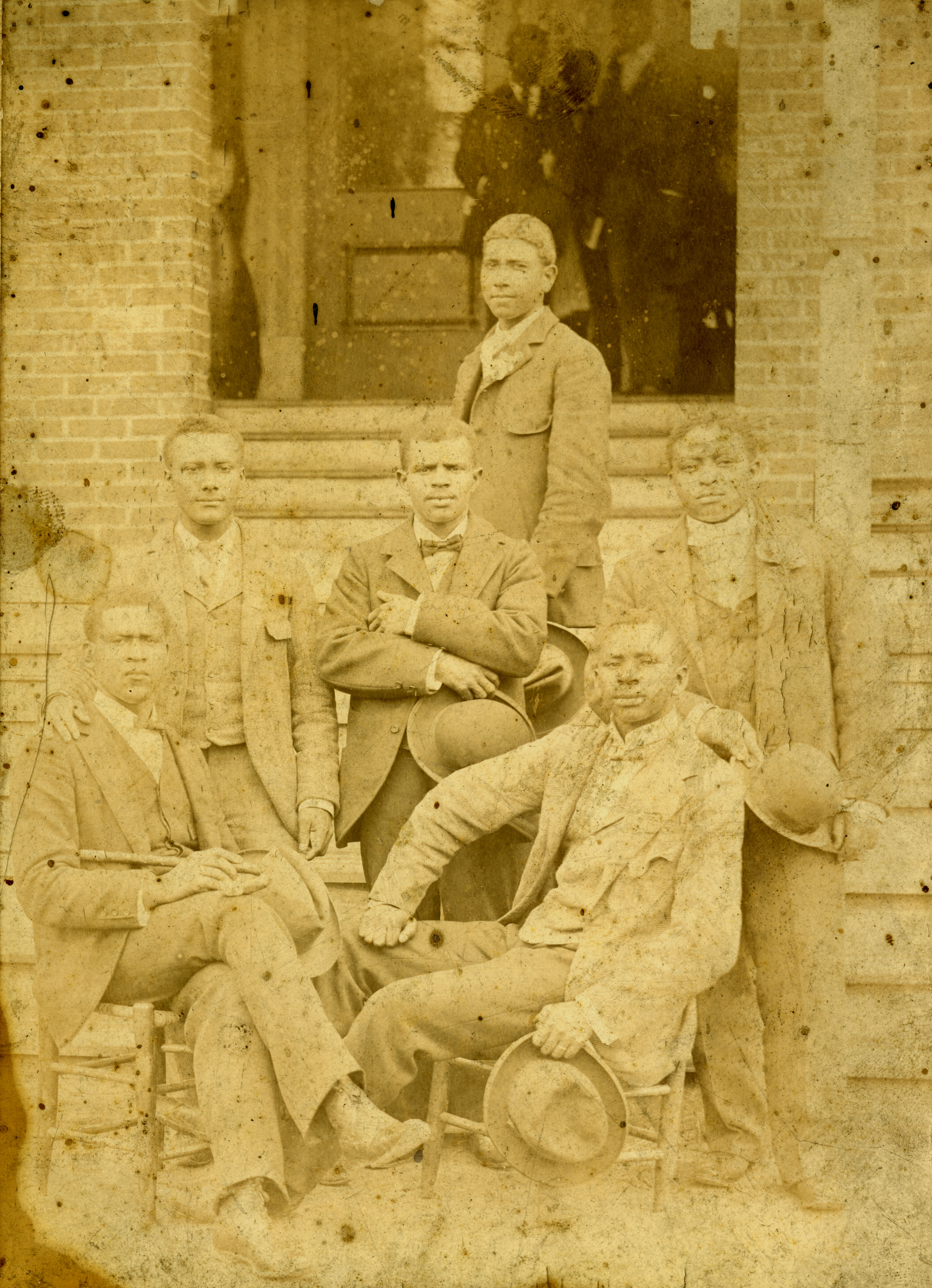

State government during Reconstruction proved vastly different than before the Civil War. The opening of the State House in November 1869 marked the start of a new era. Reconstruction broadened participation in state government. In the first legislature elected under the 1868 constitution, 75 of the 124 members of the House of Representatives and 10 of the 31 members of the Senate were African American. Many of whom are buried at the Randolph Cemetery, a national register listed historic site, which holds the distinction of being the resting place for most Reconstruction-era legislators in the country.

Among the newly empowered was William Beverly Nash, who represented Richland County in the Senate from 1868 until 1877. Born into slavery in Virginia in the early 1820s, Nash was brought to Columbia by the Preston family. During Reconstruction, he became a prominent political leader, as well as a large property owner who maintained a large farm in the city’s Wheeler Hill neighborhood and part of a brickyard. Nash’s leadership in economic development projects promoted cooperation between political opponents.

Great change and opportunity occurred on the local level, too. About half of Columbia’s city council members elected from 1870 through 1876 were African American, including merchant-tailor Robert John Palmer. Palmer was also a substantial real estate investor who owned the southeast corner of Richardson (Main) and Blanding streets, the site of today’s Tapp’s building. Palmer went on to represent Richland County in the State House of Representatives.

Beyond government, Reconstruction offered the chance for African Americans to establish their own churches, which became centers for not just spiritual enrichment but also political and social activism and strength. Among the new churches founded at that time were Ladson Presbyterian, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Zion Baptist, the Columbia Mission (later Wesley United Memorial Church) and Calvary Baptist Church.

Educationally, Reconstruction provided for the creation of a public-school system in South Carolina after 1868. By 1876, the system served 123,035 students taught by 3,068 teachers in 2,776 schools. Meanwhile, South Carolina College became the University of South Carolina, the only flagship state university to integrate during Reconstruction. Among the school’s new educators was Richard Greener, the first black graduate of Harvard University and the University of South Carolina’s first black educator.

Locally two of our most significant Historically Black Colleges and Universities were established during this era:

- With financial assistance from Rhode Island abolitionists Stephen and Bathsheba Benedict, the American Baptist Home Mission Society founded Benedict Institute in 1870 to educate freedmen and their descendants. Initially offering primary, secondary and college-level classes, the school then operated out of an antebellum plantation house.

- That same year, recognizing the growing need for an educated ministry, the African Methodist Episcopal Church established Payne Institute in Cokesbury, SC in 1870. A decade later it was relocated to Columbia and renamed Allen University in honor A.M.E. founder Bishop Robert Allen, who was born enslaved. Initially, the school ordered primary through college-level classes and both theology and law programs.

The city was physically rebuilding from its partial burning during Union occupation in February 1865 in which 1/3 of downtown was destroyed or damaged. Damaged buildings were repaired, and new structures were erected. The extent of this physical progress included, among them Reconstruction icons such as:

- the Federal Courthouse (today’s city hall)

- the South Carolina State House (which finally opened after years of work)

- the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion (established in a rehabilitated, pre-war officers’ duplex, the last vestige of Arsenal Academy)

- the Wilson family’s home on Plain Street (today’s Hampton Street)

- Further local landmarks that remain with us today, include the former Phoenix Newspaper building, in the 1600 block of Main Street, where editor Julian Selby published the first paper soon after Columbia’s burning. Selby’s Daily Phoenix was an important political tool for Democrats, who sought to shape popular opinion through its representation of “Radical Reconstruction.”

Today, visitors to Columbia and citizens alike can learn more about this watershed era through the Woodrow Wilson Family Home and the many landmark structures that remain. Moreover, through creative partnership with SCETV, Historic Columbia has been able to expand understanding about Reconstruction through an app that is currently in its beta testing phase but will soon be released by SCETV.

These plethora of sites and stories can be found throughout our state, region and country. Establishing a national park and a network, opens the doors to an even deeper understanding of the history that has yet to be fully uncovered and told.

Thank you Congressman for your leadership.

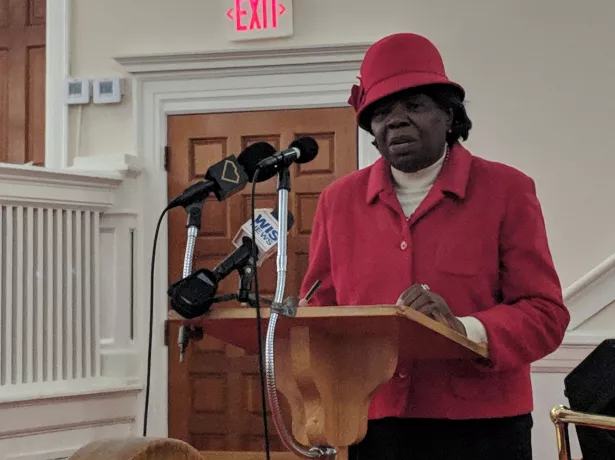

— A word from HC's Executive Director Robin Waites at the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park Act press conference held on March 4, 2019.