What We Can Learn from Woodrow Wilson, World War I and the Great Influenza

Friday, March 27th 2020

As a museum curator, working from home is difficult because I am responsible for hundreds of objects exhibited and stored throughout four historic house museums. In keeping with our mandate for social distancing, I recently moved my office into the Woodrow Wilson Family Home and Museum of Reconstruction where I can work alone, yet keep an eye on things.

With President Wilson now gazing at me daily from several exhibits, I am reminded that during his time in office he was a wartime president forced to contend with a pandemic. Now identified as the first of two outbreaks of the H1N1 virus, the Spanish Flu swept across the globe in 1918-19 during Wilson’s second term. Because our museum’s focus is on Wilson’s time in Columbia as a teenager during Reconstruction, his presidency and legacies (good and bad) are discussed, but they are not the main story.

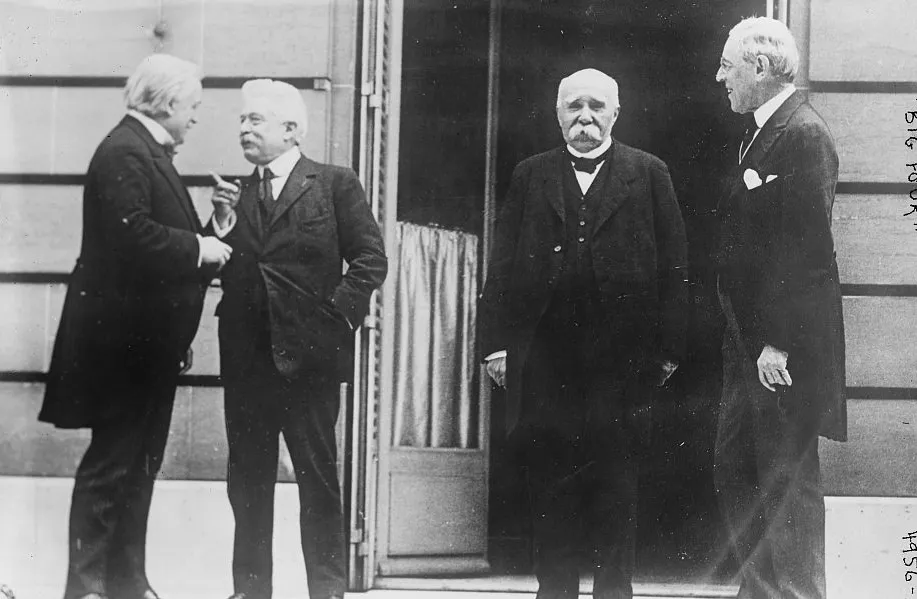

It is not normally discussed, for example, that Wilson himself contracted influenza in 1919 during the most critical part of the postwar negotiations in Paris. While France, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States were united in defeating Germany during the war, afterwards that union was severely tested as each country jockeyed for postwar power.

In his book The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, author John M. Barry relates that Wilson stood firm in his belief that to severely punish Germany would only sow the seeds of future troubles. Just before becoming ill, Wilson was so upset with negotiations that he threatened to return to the United States without a treaty.

Things changed dramatically after Wilson contracted the flu on April 3, 1919. His illness was downplayed, not for the last time, and kept from the public. After days in bed, Wilson insisted on returning to the treaty council’s negotiations despite his energy and mental ability both at the lowest his aides had ever seen. Barry writes, “Then, abruptly, still on his sickbed, only a few days after he had threatened to leave the conference … without warning or discussion with any other Americans, Wilson suddenly abandoned principles he had previously insisted upon.” The result was a treaty that Wilson told his press spokesman Ray Baker that, “If I were German, I think I should never sign it.” Sign it they did, however, and four months later Wilson’s health suffered further after a stroke that left him debilitated. Historians are left wondering what might have been different had Wilson never gotten the flu.

The effects of the Spanish Flu on families, economies, and institutions were felt for years after World War I. During one of my last visits with her, my maternal grandmother, Mary Frances, told me that during the 1918 epidemic, in her family of four, only her young sister Rebekah was unaffected. She and her parents were unable to get out of bed for weeks while Rebekah “ran wild”. If not for the care and aid from a Native American man, whose ethnicity she remembered but not his name, my grandmother remained convinced that she and her parents would have surely died.

Reflecting on the history of the Spanish Flu epidemic, one can gain some insight into how we might move forward during our current situation. President Wilson’s illness impacted his ability to make decisions and to lead. It reminds us that those in leadership positions 100 years ago were neither infallible nor immune. The same is true today. My grandmother and her parents eventually recovered, and the trials of taming young Aunt Rebekah’s newfound freedom became family legend. But it is the thought of that nameless neighbor who saved my grandmother’s life that keeps going through my mind leaving me to wonder what lessons should be learned from the first worldwide pandemic 100 years ago.

Browse through Our

Online Tours

Explore our online tours of Columbia and Richland County neighborhoods and districts. Tours can be done on your computer or turn it into a walking tour using your mobile device.