Gifts from Historic Holidays

Monday, December 3rd 2018

Diving into the imagination, playing dress up, hosting skits and talent shows for parents and friends – children have been dreaming up different ways to play for hundreds of years.

In 2018, it’s easy for a child to find entertainment. Conversely, because they did not have smartphones, video games, or TVs, children living in the mid-1800s relied heavily on creativity to entertain themselves.

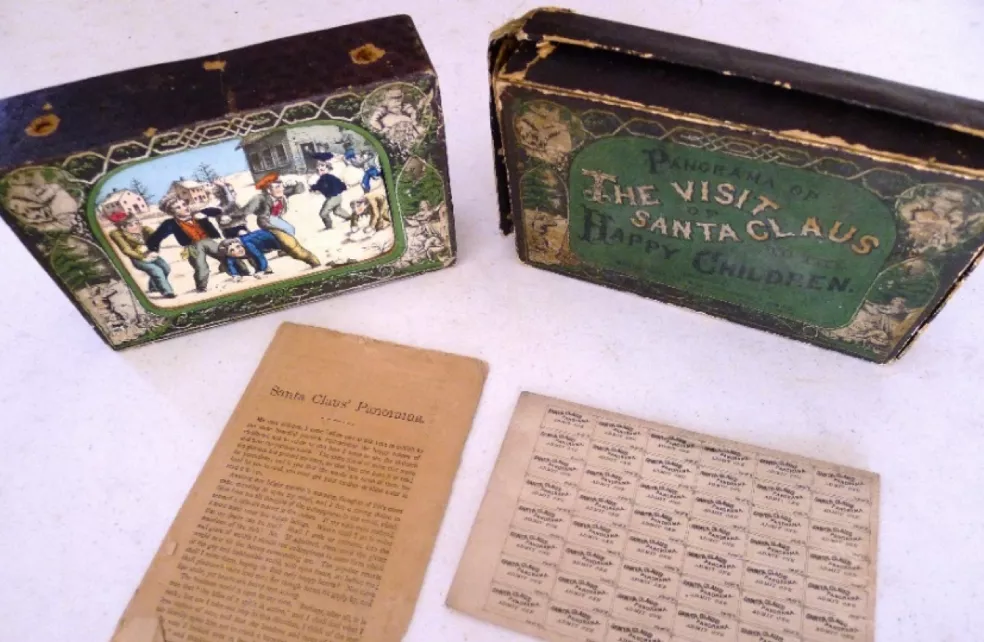

Not all children received lavish gifts on Christmas. For some families, an orange in your stocking meant Santa had been generous. However, if a family could afford it, parents may have bought their children toys like the one pictured above. “The Visit of Santa Claus to the Happy Children,” made around 1870, is an example of a moving panorama.

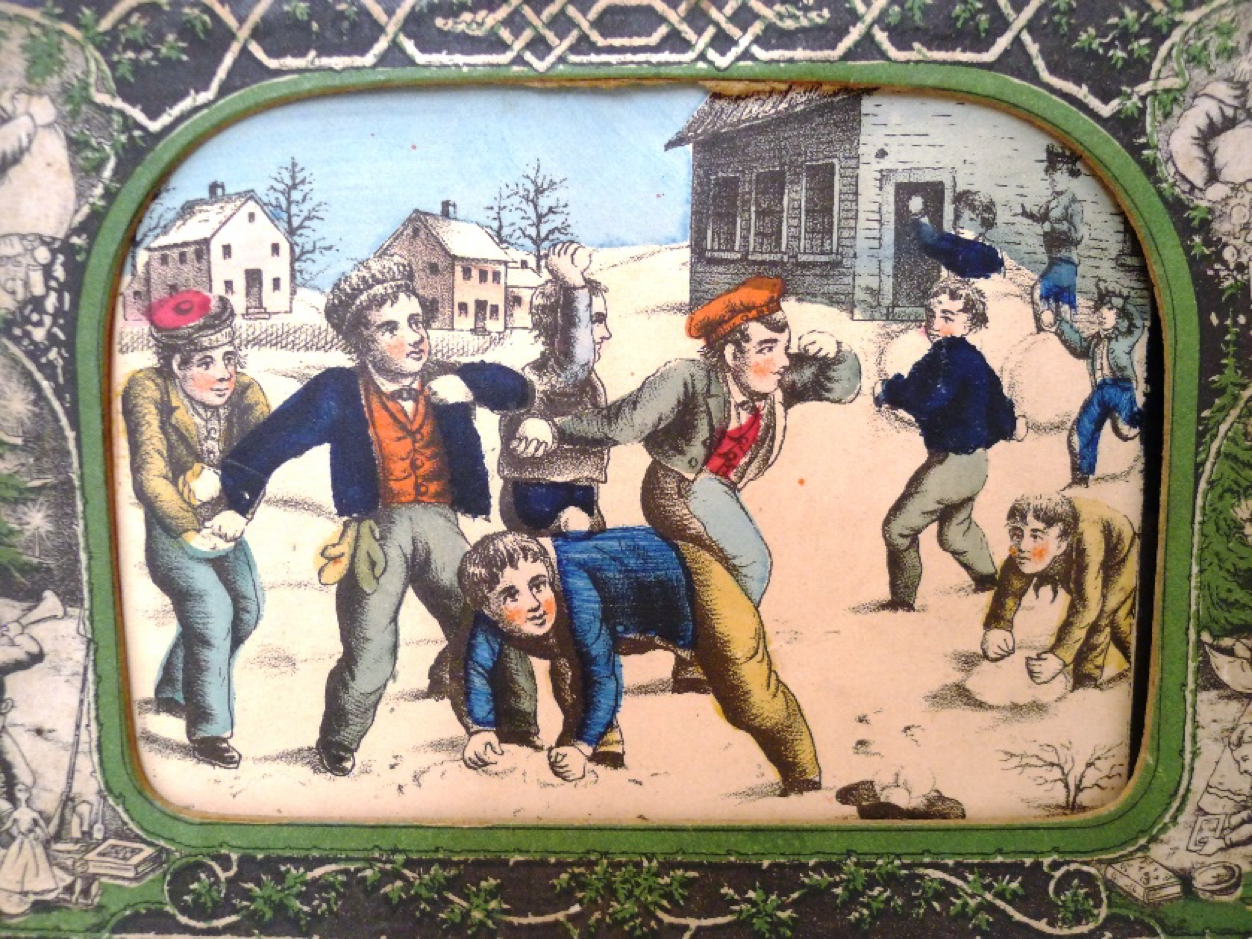

Toymakers used the latest printing technology (chromolithography) to mass-produce a series of drawings on rolls of paper. A crank on each end could move the scroll in either direction, and the children narrated the scenes that passed by. The panorama included a script that described how the main character, an adult, decided to immerse himself in the world of children and their light-hearted play in order to find happiness in life. The story culminated with a Christmas scene and the unveiling of Santa Claus as the narrator.

The manufacturer, Milton Bradley (a name associates with Christmases past, present and future) also emphasized the toy’s educational value. Some of the scenes imparted moral lessons, and the instructions encouraged children to make up their own stories if they became bored with the script. Parents could use this toy to teach reading, speaking, composition, and art.

From a child’s perspective, though, playing with a panorama was pure fun. The scroll of pictures came in an ornate box decorated to resemble a theatrical stage. Some children even used curtains to frame their “stage.”

By hiding behind these curtains, the narrator could give the illusion that he or she was invisible and that the scenes progressed on their own (almost like a movie). Spectators would receive tiny tickets to the show, which usually took place in the parlor. Parlor theatrical performances were just one way that upper- and middle-class families spent their leisure time, and children would have been delighted to receive gifts like these over the holidays.

Header image: Historic Columbia collection, HCF 00.144.1

Learn More

If you’re interested in getting a closer look at holidays past, be sure to visit the Robert Mills House and the Hampton Preston Mansion through December 30 for our Holiday House Tours.